New findings from researchers suggest Alzheimer’s disease tricks the brain into wiping out its own memories. Both sticky protein clumps known as amyloid beta and brain swelling target the same spot on nerve cells, telling them to cut vital links needed for recall. This work, done at Stanford, points to a common path that destroys memory and opens doors to new treatments.

Background

Alzheimer’s hits millions worldwide, stealing memories bit by bit. Patients first forget recent events, then faces and daily tasks fade away. For years, doctors focused on amyloid beta, those protein bits that build up into plaques between brain cells. Drugs like lecanemab aim to clear these plaques, slowing decline a touch. But memory does not come back. Many experts now look at other causes, like swelling from the body’s immune response in the brain.

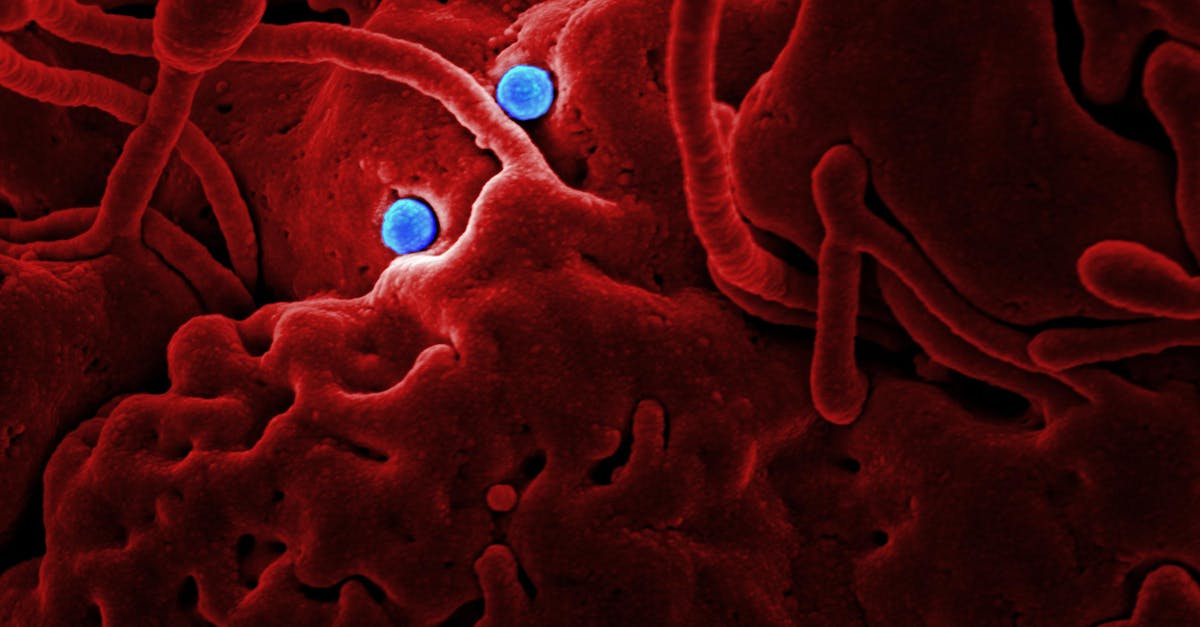

This swelling, or inflammation, ramps up as Alzheimer’s worsens. Immune cells release signals that harm healthy tissue. Past studies linked both amyloid beta and inflammation to lost connections between neurons, called synapses. Synapses let brain cells talk, forming the web of memory. When they go, so does recall.

Stanford scientists built on old work about a receptor called LilrB2. Back in 2006, they found its mouse version helps prune synapses during growth and learning. Pruning shapes the brain, but too much hurts. By 2013, tests showed amyloid beta sticks to LilrB2, sparking synapse loss. Mice without this receptor kept memories better in Alzheimer’s models.

Key Details

The new study ties amyloid beta and inflammation to LilrB2 in a clear way. Researchers screened immune proteins from the complement system, which fights invaders but can backfire in the brain. One piece, C4d, bound tight to LilrB2.

To check, they injected C4d into healthy mouse brains. Synapses vanished fast.

"Lo and behold, it stripped synapses off neurons," said Carla Shatz, a biology professor at Stanford who led the work.

This molecule was once seen as useless junk. Now it looks key to damage.

How the Switch Works

LilrB2 sits on neurons like a signal receiver. Amyloid beta docks there first, then C4d from inflammation piles on. Both flip the switch, ordering synapse removal. Neurons follow, pruning links they need for memory. It is not passive harm—cells do the work themselves.

Tests used Alzheimer’s mouse models with human-like symptoms. Blocking LilrB2 saved synapses and memory. Separate UCLA work fits here. They made a molecule, DDL-920, that boosts brain rhythms tied to recall. Given to sick mice for two weeks, it fixed maze memory to normal levels. No odd side effects showed.

Gamma waves, fast electrical pulses from certain neurons, drive memory. In Alzheimer’s, these weaken. DDL-920 eases brakes on those neurons, ramping waves back up. Lead researcher Istvan Mody noted current plaque drugs leave brain circuits broken.

“They leave behind a brain that is maybe plaqueless, but all the pathological alterations in the circuits and the mechanisms in the neurons are not corrected,” Mody said.

Other teams target related paths. One group used gene tools to tweak aging brain chemicals, boosting rat memory. Another hit an inflammation enzyme in risky mice, calming brain swelling.

What This Means

This shared switch changes how we see Alzheimer’s. It links top theories—amyloid and inflammation—into one path. Drugs hitting LilrB2 or like receptors might shield synapses directly, saving memory outright.

Past treatments slow loss but do not fix it. A synapse protector could differ. Mice without LilrB2 or on DDL-920 recalled paths, nests, fears like healthy ones. Human trials lie ahead, testing safety and reach across the blood-brain wall.

Broader reach shows too. Weak gamma waves link to depression, schizophrenia, even autism. If this works, one drug might aid many. Inflammation paths deserve more eyes, as Shatz put it. They may drive loss unchecked.

Teams plan next steps. UCLA eyes human safety for DDL-920. Stanford pushes LilrB2 blockers. Gene tweaks from other labs hint multiple fixes fit together. For now, mice prove the point: flip the switch off, memories stay.

Patients wait. Over 6 million in the US face Alzheimer’s now. By 2050, numbers may double. Each step like this brings tools closer. Families see hope in brains that fight back, not just slow foes.