Scientists at the University of Nottingham and the University of Cambridge have found that the brain uses nearly the same areas to remember facts and to recall personal events. The team used brain scans on 40 people and saw no clear difference in activity between the two memory types. This result goes against years of research that treated these memories as separate. The work came out this week and could change how experts study memory problems in diseases like Alzheimer's.

Background

For a long time, scientists split memory into types. One type is episodic memory. This lets people remember events from their own lives, like what they ate for breakfast or a trip to the beach. The other is semantic memory. This holds general facts, such as knowing that Paris is the capital of France or that water boils at 100 degrees Celsius.

Experts thought these worked in different brain parts. Episodic memory was linked to areas that handle personal experiences and time. Semantic memory was tied to spots for facts and knowledge. Studies over decades built this view. They often tested one type at a time, so few checked both side by side.

This split shaped textbooks and research. It guided tests for memory loss in older people. Doctors used it to spot early signs of dementia. But no one had directly compared the brain activity for both in the same careful setup. That gap left room for doubt.

The new study fills that space. It comes from teams in two UK universities. They wanted to test if the brain really keeps these memories apart. Their work builds on tools that map brain activity in real time.

Key Details

The researchers brought in 40 healthy adults. They created tasks to test both memory types. First, everyone learned pairings of made-up logos and brand names. These were new, so they tested episodic memory. Later, people saw real logos like Nike or Apple. They recalled facts about them from what they already knew. This tested semantic memory.

Both tasks were very similar. People saw a logo and tried to name the brand. For episodic, they pulled from the study session. For semantic, they used lifelong knowledge. This matching made the test fair.

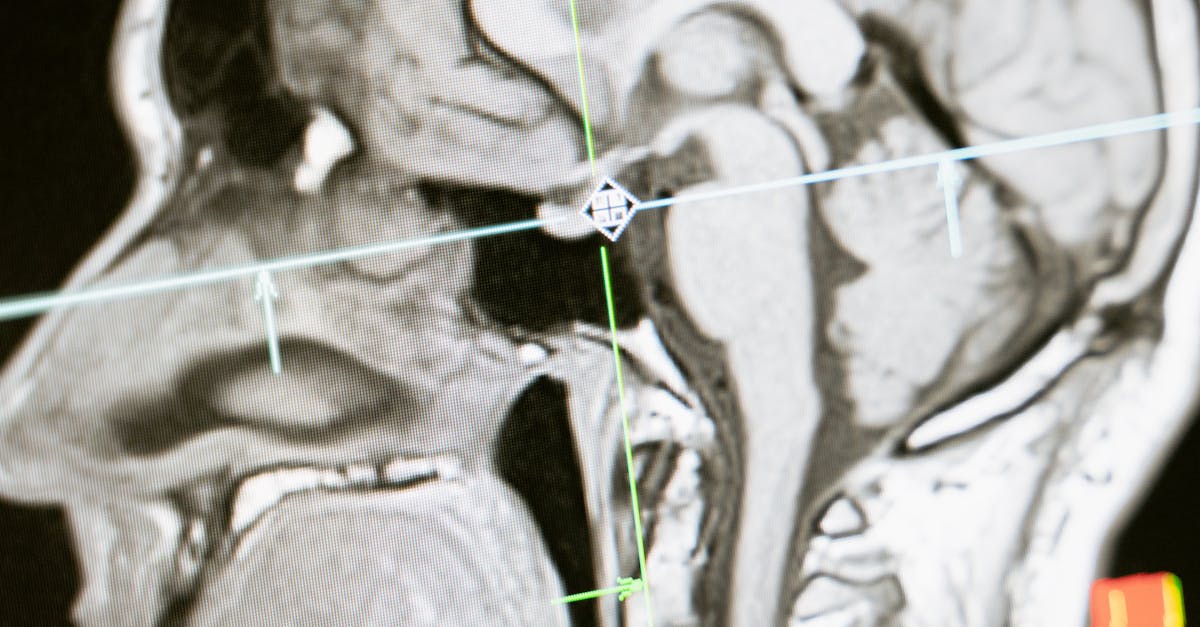

While people did the tasks, they lay in an fMRI machine. This tool tracks blood flow in the brain. Active areas get more oxygen-rich blood. The machine makes 3D maps of that flow. It shows exactly which spots light up during thinking or remembering.

The scans showed a surprise. Brain activity looked almost the same for both tasks. Key networks overlapped a lot. There were no big differences where experts expected them. The patterns held steady across all 40 people.

How fMRI Works in This Study

fMRI gives clear pictures without harm. It spots changes as small as blood flow shifts. In this case, it captured moments of successful recall. Both memory types fired up the same hubs. These include areas in the middle of the brain that link ideas and experiences.

Dr. Roni Tibon led the work. She is an assistant professor at Nottingham's School of Psychology.

"We were very surprised by the results of this study as a long-standing research tradition suggested there would be differences in brain activity with episodic and semantic retrieval. But when we used neuroimaging to investigate this alongside the task based study we found that the distinction didn't exist and that there is considerable overlap in the brain regions involved in semantic and episodic retrieval." – Dr. Roni Tibon

Her team ran checks to confirm the data. They matched tasks closely to avoid bias. Results stayed strong.

What This Means

This finding shakes up memory science. Textbooks may need updates. Instead of two clear systems, memory looks more like one big network. Facts and events blend in the brain. Recalling a birthday party might tap the same spots as knowing a math fact.

For diseases, it points to new paths. Alzheimer's hits memory hard. Patients lose events first, then facts. If both use shared areas, damage in those spots explains both losses. Early tests could scan whole networks, not just parts.

Treatments might target the full system. Drugs or training could boost overlapping regions. This view sees the brain as a team player, not split teams. It matches how people remember in daily life. A story often mixes facts and feelings.

Other work supports this shift. Past studies hinted at overlap but lacked direct proof. This one delivers that with solid scans. It calls for more tests across ages and health states.

Experts outside the team note the impact. One Cambridge researcher not involved said it bridges gaps in old models. Wider studies could follow, using the same methods on patients.

The paper spells out next steps. Teams plan to test in people with mild memory issues. They want to see if overlap holds or breaks in disease. Scans on kids and older adults could show how networks change over life.

This work also aids brain mapping tools. fMRI details help plan surgeries or track recovery. Better memory maps mean sharper care.

Daily life feels the echo. People mix memories all the time. Work meetings blend known skills with fresh notes. This study mirrors that reality. It suggests the brain wires for flexible recall, not rigid boxes.

As research grows, it could reshape clinics. Doctors might use simpler tests that hit both memory types. Families of patients could get clearer advice on what to expect.

The Nottingham and Cambridge link shows team science at work. Shared data and tools speed finds. More groups may join to build on this.