Researchers at the National University of Singapore's medical school have found a protein called DMTF1 that can help aging brain cells start regenerating again. The team showed this works in human cells and lab models that mimic early aging. They reported their results this week after years of testing how brain cells lose their ability to renew as we get older. The work focuses on neural stem cells, which make new neurons needed for memory and learning. Without enough of these new cells, the brain struggles with age-related changes.

Background

As people age, the brain changes in ways that affect daily life. Neural stem cells, found in areas like the hippocampus, normally produce new neurons to help with learning and memory. Over time, these cells slow down and stop dividing as much. This leads to fewer new brain cells, which ties into problems like forgetfulness and slower thinking.

One big factor in this slowdown is telomeres. These are caps at the ends of chromosomes that protect DNA. Each time a cell divides, telomeres get a bit shorter. When they wear down too much, cells act old, even if the person is not very old yet. Scientists have known for years that short telomeres harm neural stem cells. But until now, they did not fully understand how to fix this problem.

The NUS team started looking at proteins that control cell growth. They used cells from humans and mice set up to age fast. These models let them see what happens in real aging without waiting decades. They checked gene activity and how proteins bind to DNA. This helped them spot DMTF1 as a key player. In young brains, DMTF1 shows up at higher levels. In older cells, it drops off.

Past studies have linked poor neural stem cell renewal to brain aging. Some work restored this renewal partly, but no one knew the main reasons why. This new research fills that gap by pointing to DMTF1.

Key Details

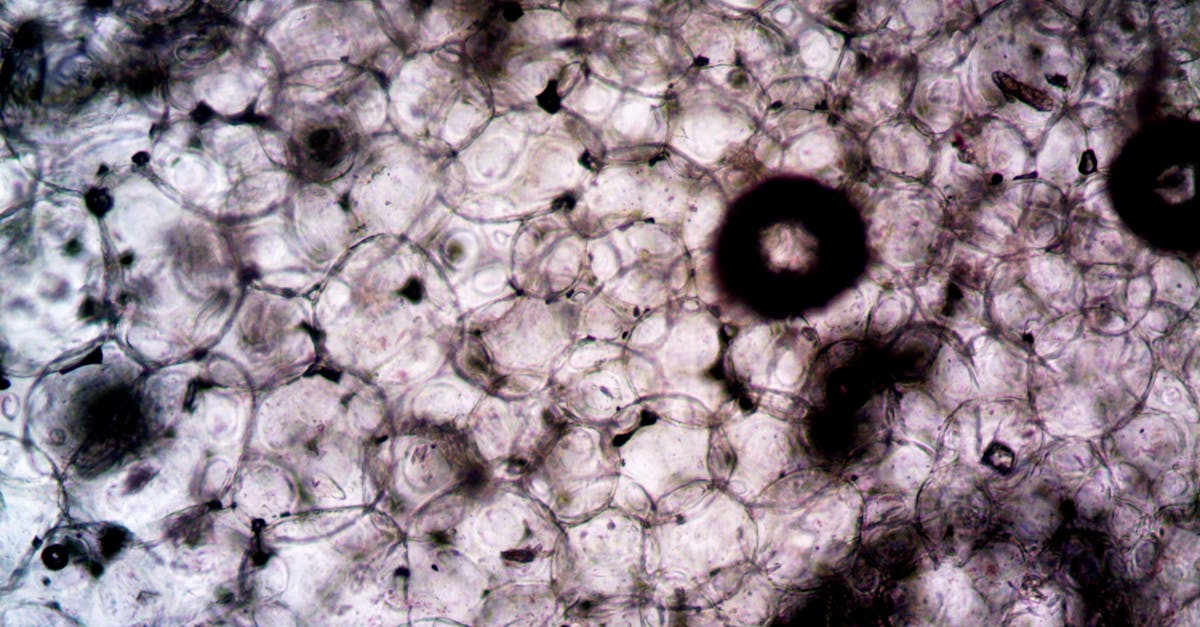

The researchers tested neural stem cells from humans and lab animals with short telomeres. They found DMTF1 levels were low in these aged cells. When they added more DMTF1, the cells started dividing and growing again. This happened even though the telomeres stayed short. Boosting DMTF1 alone was enough to bring back the cells' renewal power.

How DMTF1 Works

DMTF1 acts like a switch for other genes. It turns on two helper genes: Arid2 and Ss18. These helpers loosen up the DNA, which is packed tight in old cells. Once loose, growth genes can turn on. This starts a chain that lets stem cells multiply and make new neurons. Without DMTF1, the helpers do not work, and cells stall out.

The team used tools like genome binding analysis to map this process. They saw DMTF1 bind to spots that control these helpers. Transcriptome analysis showed changes in gene activity after adding DMTF1. In tests, cells with more DMTF1 grew into spheres, a sign of healthy stem cells. They also made more proteins like MCM2, which marks dividing cells, and SOX2, a stem cell marker.

The study stuck to lab dishes and animal models. No live human brains were involved yet. But the results held up across human and mouse cells.

"Our findings suggest that DMTF1 can contribute to neural stem cell multiplication in neurological aging," said Dr. Liang Yajing, a neuroscientist on the team. "While our study is in its infancy, the findings provide a framework for understanding how aging-associated molecular changes affect neural stem cell behavior, and may ultimately guide the development of successful therapeutics."

"Impaired neural stem cell regeneration has long been associated with neurological aging," said Assistant Professor Ong. "Inadequate neural stem cell regeneration inhibits the formation of new cells needed to support learning and memory functions."

What This Means

This discovery opens doors to treatments that could slow brain aging. Drugs or methods to raise DMTF1 levels might help older neural stem cells work like they did when young. This could mean better memory and learning for older people. It might also help those with early aging conditions tied to short telomeres.

The team sees DMTF1 as a good target for therapy. Ways to boost its expression or activity could delay the drop in stem cell function. Right now, the work is mostly from cell cultures. Next steps include tests in live animals with natural aging or telomere issues. They want to check if more DMTF1 increases stem cell numbers and fixes learning problems. A big concern is avoiding brain tumors, since too much cell growth can lead to that.

Long-term, the group aims to find small molecules that turn up DMTF1 safely. These could be pills or injections to help aged brains. The findings also shed light on how aging changes gene control in the brain. Other researchers might build on this for wider aging treatments.

Neural stem cells sit in special zones of the adult brain. They keep a pool of cells ready to become neurons when needed. As telomeres shorten with each division, this pool shrinks. DMTF1 seems to bypass some of that damage by working through its helper pathway. This workaround could be key for therapies.

The study adds to a growing list of work on brain renewal. Other teams have tried factors like growth hormones, but with mixed results. DMTF1 stands out because it directly fixes the renewal block in aged cells. If animal tests pan out, human trials could follow in coming years.

Experts outside the team note the promise but call for more data. Brain aging involves many factors beyond stem cells, like inflammation and blood flow. Still, restoring neuron production could make a real difference. For now, the work stays in labs, but it points to real hope for healthier aging brains.