Scientists at the University of Geneva have found that tumors can change neutrophils, a type of immune cell, so they help cancer grow instead of stopping it. These cells start making a protein called CCL3 when they enter the tumor area. The work points to new ways to track how cancers worsen over time.

Background

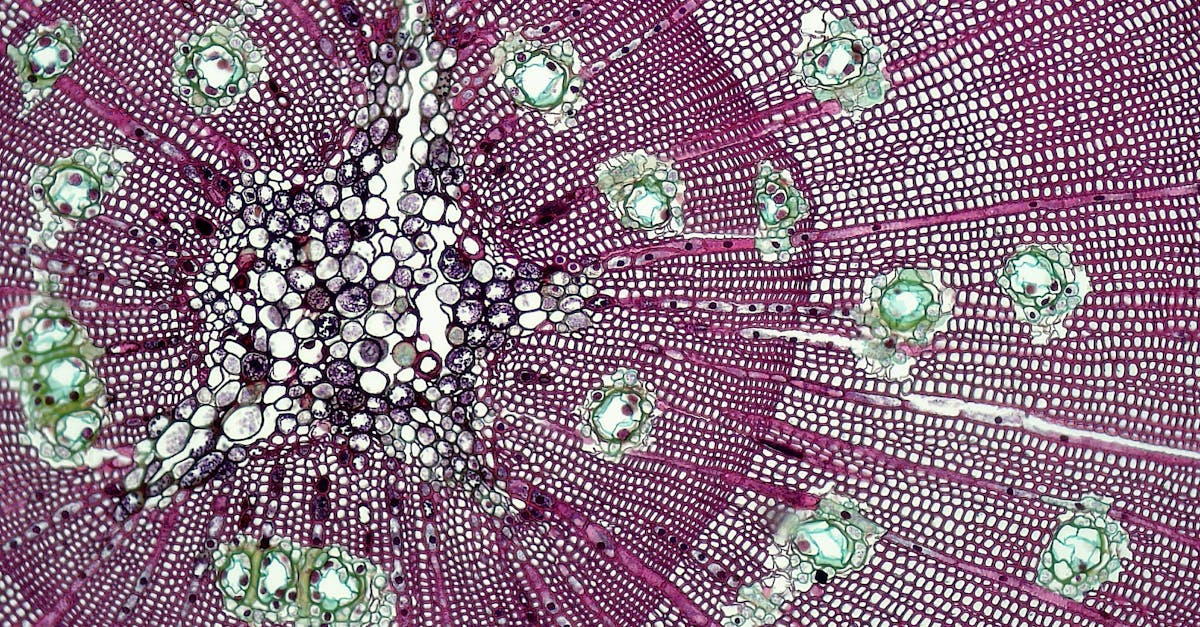

Neutrophils are white blood cells that rush to fight infections and heal wounds. They make up a big part of the body's defense system. In healthy people, these cells spot germs and break them down. Doctors have long known that neutrophils show up in tumors, but their role there was not clear. Some studies suggested they might help tumors, but no one knew exactly how.

This new research builds on earlier work from the same team. In 2023, they looked at macrophages, another immune cell, and found two genes that linked to worse cancer outcomes. That gave doctors a way to guess how a tumor might act. Now, the focus is on neutrophils. The team worked with the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to study tumors in people and mice.

They looked at over 190 tumors from different cancers. The goal was to see what happens when neutrophils meet cancer cells. Tumors create a special space around them, full of low oxygen and signals that change nearby cells. Neutrophils get pulled into this space, but instead of attacking, they change.

The study used mouse models and human tumor samples. Researchers also checked data from many past studies. Neutrophils are hard to study because they do not make much genetic material, so they are easy to miss. The team made new tools to find them better.

Key Details

When neutrophils reach the tumor, they shift into a new state. They start making high levels of CCL3, a small protein that acts as a signal. CCL3 draws in more cells and helps tumors grow blood vessels and spread. Without CCL3, neutrophils stay in tumors but stop helping cancer.

How They Proved It

The researchers changed neutrophils in mice so they could not make CCL3. They used special methods to target only these cells, leaving others alone. Tumors grew slower in these mice. The neutrophils still went to the tumor sites and worked normally in the blood, but they lost their harmful side.

They also built a new computer tool to spot neutrophils in genetic data. This showed the same pattern in many cancers: neutrophils end up in a state where they pump out CCL3. This state links to older neutrophils that adapt to low oxygen areas in tumors.

"We discovered that neutrophils recruited by the tumour undergo a reprogramming of their activity: they begin producing a molecule locally—the chemokine CCL3—which promotes tumour growth," said Mikaël Pittet, lead researcher at the University of Geneva.

Evangelia Bolli handled the lab work. She said getting CCL3 control just right was tough. Pratyaksha Wirapati led the data analysis. He noted neutrophils are often overlooked because they are quiet on the genetic level.

"We had to innovate to detect neutrophils more accurately," said Pratyaksha Wirapati. "Their low genetic activity often makes them invisible using standard analysis tools."

The CCL3 state shows up across cancers like lung, breast, and prostate. It matches with worse outcomes for patients. In mice and humans, these neutrophils cluster in low-oxygen spots, where tumors hide from the immune system.

What This Means

This finding gives doctors a new sign to watch tumor growth. Levels of CCL3 from neutrophils could tell if a cancer will get worse fast. It might help pick treatments for each patient. Right now, predicting cancer paths is hard. Many tumors look the same at first but act differently later.

The work suggests tumors keep these changed neutrophils alive with CCL3 signals. Blocking CCL3 or its receiver, CCR1, might stop this help. In mice, cutting CCL3 slowed tumors without harming normal neutrophil jobs. This could lead to drugs that fix the immune response.

Experts see this as part of a bigger picture. Tumors have a few key players that drive their path. The 2023 macrophage genes were one set. Neutrophils and CCL3 make another. Finding all these could create a full profile for each tumor, like an ID card.

"We are deciphering the 'identity card' of tumors, by identifying, one by one, the key variables that determine the evolution of the disease," Pittet explained.

More tests are needed to see if this works in people. The team plans to check CCL3 in blood or tumor samples. If it predicts outcomes well, it could change how doctors watch and treat cancer. This might mean fewer surprises and better plans for patients facing tough diagnoses.

The study adds to efforts to map the area around tumors. That space holds many cells that tumors use. Understanding neutrophils opens doors to new therapies. For now, it shows how cancer turns friends into foes in the body.