Researchers at Princeton University have discovered that a common vitamin A byproduct quietly disarms the immune system, giving tumors a way to escape detection and attack. The finding explains a long-standing medical puzzle about why vitamin A supplements appear harmful despite being studied as a potential cancer fighter for decades.

The molecule responsible is called all-trans retinoic acid. It is produced naturally in the body and has been used medically to treat certain blood cancers. But new research shows it also works against the body's defenses when it comes to fighting solid tumors.

Scientists have now created a drug called KyA33 that blocks this process. In animal studies, the compound restored immune function and slowed cancer growth. The findings were published in the journal Nature Immunology and represent what researchers describe as a major breakthrough in targeting a biological pathway that has resisted drug development for more than 40 years.

Background

Vitamin A has long occupied an odd place in cancer research. Laboratory experiments show that retinoic acid, the active form of vitamin A in the body, can stop cancer cells from growing or cause them to die. This led scientists to believe that vitamin A might help prevent cancer.

But large clinical trials told a different story. People who took high-dose vitamin A supplements actually had higher cancer rates and higher death rates from all causes. Tumors with high levels of the enzymes that produce retinoic acid were also linked to worse survival outcomes across many cancer types.

This contradiction puzzled researchers for years. How could a substance that kills cancer cells in a dish actually make cancer worse in real people? The answer, it turns out, involves the immune system.

Key Details

How Retinoic Acid Weakens Immune Defense

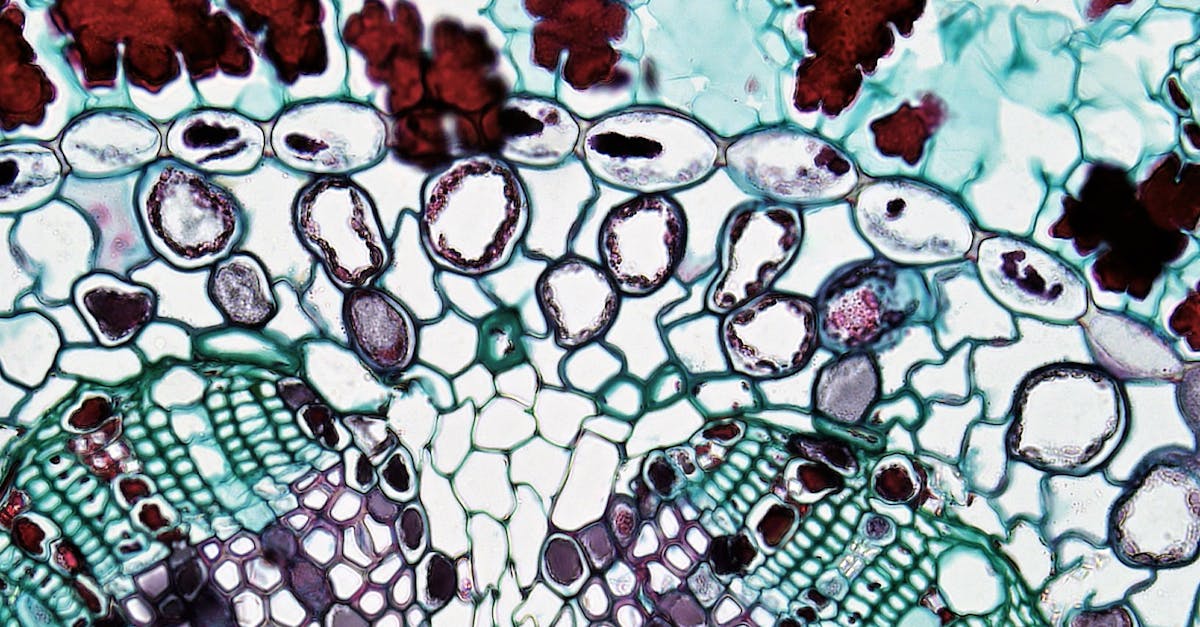

The immune system relies on special cells called dendritic cells to sound the alarm when cancer appears. These cells act as scouts, identifying cancer cells and alerting T cells to attack them. They are so important that scientists have spent years developing vaccines based on dendritic cells as a potential cancer treatment.

But the research team found that retinoic acid reprograms these immune cells in a dangerous way. When dendritic cells produce high levels of retinoic acid, they lose their ability to activate the immune response. Instead, they develop a tolerance toward tumors, essentially telling the immune system to stand down.

"We discovered that under conditions commonly employed to produce DC vaccines, differentiating dendritic cells begin expressing ALDH1a2, producing high levels of retinoic acid," said Cao Fang, a graduate student who led much of the research. "The nuclear signaling pathway it activates then suppresses DC maturation, diminishing the ability of these cells to trigger anti-tumor immunity."

This happens during the very process used to manufacture dendritic cell vaccines. The conditions that doctors use to prepare these vaccines actually trigger the production of retinoic acid, which then sabotages the vaccine's effectiveness. This previously unknown mechanism may explain why dendritic cell vaccines have performed poorly in human trials despite showing promise in early tests.

The Cancer Cell Strategy

Tumors themselves also exploit this weakness. Cancer cells produce high levels of the enzyme ALDH1a3, which generates retinoic acid. But unlike normal cells, cancer cells have evolved to ignore the signals that retinoic acid sends. They are immune to its growth-stopping effects.

Instead, the retinoic acid they produce enters the tumor microenvironment—the tissue surrounding the cancer—where it suppresses T cells and other immune defenses. This allows tumors to hide in plain sight, protected by a chemical cloak made from a nutrient the body needs.

The New Drug

The research team developed KyA33 to block the production of retinoic acid by both cancer cells and dendritic cells. In mouse models of melanoma, vaccines created with KyA33 generated strong immune responses that delayed tumor development and slowed cancer growth.

When given directly to mice, KyA33 also worked as a standalone treatment, reducing tumor growth by stimulating immune function. The drug represents the first successful inhibitor of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, a biological system that had resisted drug development since it was first discovered in the 1980s.

What This Means

The discovery solves the vitamin A cancer paradox and opens new treatment possibilities. It explains why high vitamin A intake increases cancer risk—the body is essentially providing tumors with the raw materials to suppress immune defenses.

For cancer treatment, the findings suggest that blocking retinoic acid production could make existing immunotherapies work better. Dendritic cell vaccines might finally deliver on their promise if given alongside KyA33. The drug could also enhance other immune-based treatments that rely on T cell function.

The research also highlights how cancer exploits normal biological processes for its own survival. Tumors did not invent retinoic acid's immune-suppressing abilities. They simply hijacked a system that the body uses naturally. Understanding these hijacking mechanisms is opening new avenues for cancer treatment.

The work is still in preclinical stages. KyA33 has not yet been tested in humans. But researchers say the approach provides a framework for developing other drugs that target pathways cancer has learned to exploit. The next step will be moving toward human trials to see if the promise shown in animals translates to real patients.