Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin have found that El Niño and La Niña, part of a climate pattern called ENSO in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, drive floods and droughts across the world at the same time. Their study, based on satellite data from 2002 to 2024, shows these events push distant areas into wet or dry conditions together. This pattern has grown stronger over the past two decades, with dry spells becoming more common since around 2012.

Background

ENSO swings between El Niño, with warmer ocean waters, and La Niña, with cooler waters. These changes affect weather patterns far from the Pacific. For years, scientists have known they influence rain and dry spells in places like South America, Australia, and Africa. But this new work looks at total water storage across the globe—water in rivers, lakes, soil, snow, and underground.

The team used satellites called GRACE and GRACE-FO, launched by NASA. These measure changes in Earth's gravity caused by water movement. They track water over areas about the size of Indiana, roughly 300 to 400 kilometers across. From 2002 to 2024, the data covered 22 years, enough to spot patterns in wet and dry extremes.

Wet extremes mean water levels above the 90th percentile for a region—unusually high. Dry extremes are below the 10th percentile—unusually low. Before 2011, wet extremes happened more often. After 2012, dry ones took over. This switch lines up with a long-term change in Pacific climate that boosts ENSO's dry effects.

Past events show the links. In the mid-2000s, an El Niño brought severe drought to South Africa. The 2015-2016 El Niño hit the Amazon hard with dryness. On the flip side, the 2010-2011 La Niña soaked Australia, southeast Brazil, and South Africa with heavy rain.

Key Details

The study marks the first time researchers tracked total water extremes tied to ENSO worldwide. Past work focused on counting rare events or their strength, but extremes are too few for clear trends. Instead, this team mapped how they connect across space, giving a fuller picture.

ENSO does not always cause the same conditions everywhere. In some spots, El Niño brings dry weather; in others, La Niña does. Wet weather follows the opposite. For instance, El Niño dried out parts of South Africa and the Amazon, while La Niña flooded Australia and Brazil.

Satellite Data and Gaps

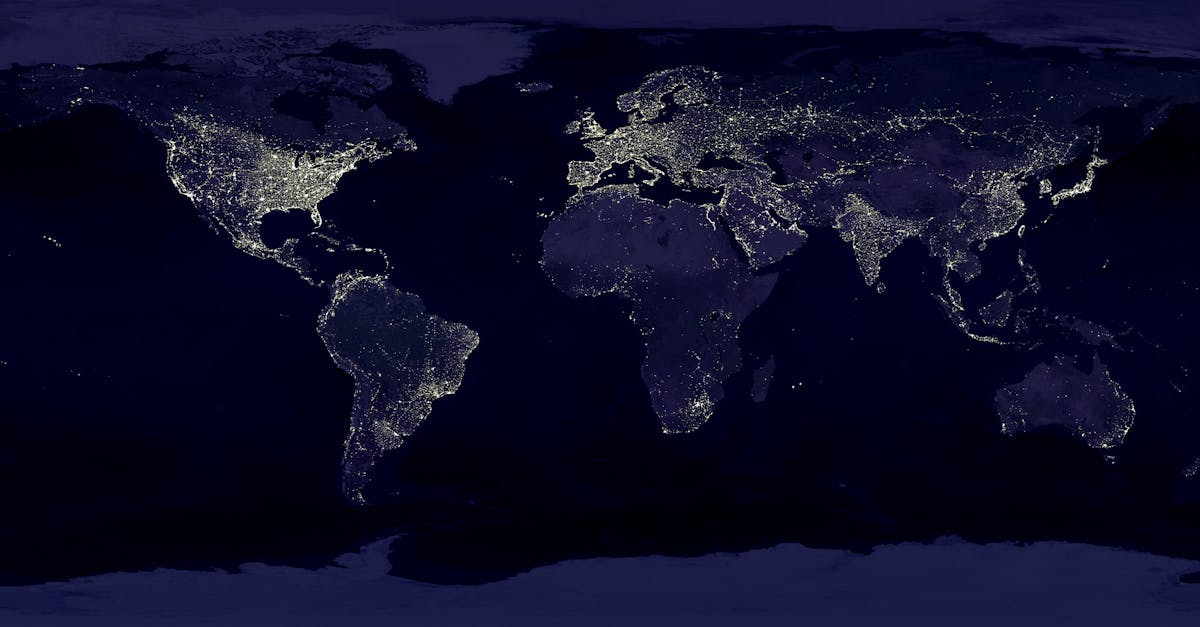

GRACE ran from 2002 to 2017, with an 11-month break before GRACE-FO took over. The team filled gaps with models based on space patterns. This let them see ENSO's reach across continents. The data shows abnormal ENSO activity lines up dry or wet spells in far-apart places, like North America and Asia, or Europe and Australia.

Lead author Ashraf Rateb, a research assistant professor, explained the approach.

"Most studies count extreme events or measure how severe they are, but by definition extremes are rare. That gives you very few data points to study changes over time. Instead, we examined how extremes are spatially connected, which provides much more information about the patterns driving droughts and floods globally." – Ashraf Rateb

Co-author Bridget Scanlon added that global views help spot linked areas.

"Looking at the global scale, we can identify what areas are simultaneously wet or simultaneously dry. And that of course affects water availability, food production, food trade—all of these global things." – Bridget Scanlon

ENSO has become the main driver of these water swings over the last 20 years. Its synchronizing power means one strong event can strain resources in multiple spots at once.

What This Means

Water crises now look like part of a worldwide system, not local problems. When dry extremes hit many places together, food production drops, trade shifts, and aid needs rise. Wet extremes can flood farms and cities far apart, overwhelming response efforts.

The rise in dry extremes since 2012 points to bigger drought risks. Areas like the Greater Horn of Africa and parts of South America have seen long dry spells tied to La Niña. South Africa and the Amazon faced El Niño droughts. Australia got floods from La Niña.

This work stresses managing ups and downs in water, not just scarcity. Communities need plans for linked events. Farmers in wet zones during one ENSO phase might export food, but dry phases elsewhere could flip that. Governments track ENSO forecasts to prepare.

JT Reager, a NASA scientist on GRACE-FO, noted the big picture.

"Oftentimes we hear the mantra that we're running out of water, but really it's managing extremes. And that's quite a different message." – Bridget Scanlon

Looking ahead, current weak La Niña may fade by early 2026, with neutral conditions or El Niño possible later. Neutral times bring steadier weather, but any ENSO swing could sync new extremes. The study calls for better global monitoring to handle these patterns.